by Norman Ball

Bright Lights Film Journal

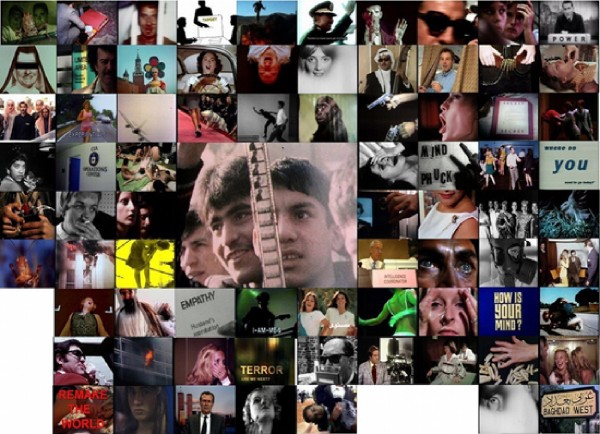

Before this essay interrogates Adam Curtis' hidden vestibules, gimpy tripods, and grassy knolls, I'd like to say that any book or film that keeps me thinking a year after I encounter it passes my substantiality test. The Power of Nightmares and The Century of the Self easily fit this category. (I saw All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace, The Living Dead, and bits of The Trap only last week.) To survive the immediate frame of the modern attention span is to escape the charge of empty spectacle. You can't fake sustained recollection.

Substance need not equate to wholesale affirmation, however. A good polemic dusts off the thinking caps even of its opponents. Curtis' films provide, at the very least, dialectical lightning rods for alternate narrative threads. Can the same be said for (insert any American TV show)?

In recent weeks Curtis has been arguing for television (BBC being the originating medium for his documentary films, though an American audience can view them on Youtube and Vimeo) to refashion its storytelling techniques ("Adam Curtis Argues TV Needs 'New Tools' to Tell Its Stories," The Guardian, August 22, 2012). It should be fascinating to see where Curtis' films conduct television in the coming months and years. Now, if we could only get American TV to mosey on over to where Curtis has already been, that would be advancement indeed. Right now, stateside viewers are All Kvetched Over by Whole Reams of Will and Grace, but only on DVD due to some contractual disputes that preclude syndication and broadcast. Curtis offers many of his films for free on the Internet. Need I kvetch more?

The award-winning The Century of the Self (2002) offers a devastating critique of our subliminal cooptation from a lifetime's exposure to "father of public relations" Eddie Bernays' propaganda techniques. Whoops, did I just say propaganda? Bernays' most diligent pupil, Josef Goebbels, is rolling over in his hell-pit right now. Let's leave it at public relations. I'm particularly fond of Bernays' quote (very crudely paraphrased here) that democracy is a wonderful system so long as he, Bernays, exerted final subliminal pull over the lever pulled inside the voting booth. Historian Carroll Quigley (mentor of a certain Rhodes Scholar, Bill Clinton), upon being made privy to the papers of the American elite, realized that nothing was left to chance, not even 50-50 propositions. In what's often referred to as the Quigley Principle, this Georgetown professor torpedoed the notion of a vigorous two-party system. Both levers are vetted and fixed. Here he is paraphrasing the mindset of the government behind the government: "The argument that the two parties should represent opposed ideals and policies, one, perhaps, of the Right and the other of the Left, is a foolish idea acceptable only to the doctrinaire and academic thinkers. Instead, the two parties should be almost identical, so that the American people can 'throw the rascals out' at any election without leading to any profound or extreme shifts in policy" (Carroll Quigley, from Tragedy and Hope).

This is not a call to embrace monolithic conspiracy theories. There often is, as Quigley went on to suggest, dissension at the highest levels of power. Jealousy is after all a facet of power. Bernays too saw the value of ostensible choice in a democratic-capitalist system where everything boils down to packaging anyway. A typical Bernays adBy the end of WWII, needs in America had, by and large, been put to bed. Desire was the ultimate lever, a grail of incalculable dual potential. Freud's irrational man, with his limitless storehouse of appetites and anxieties, would furnish economic growth ad infinitum. Never mind that natural resources such as oil and copper are ultimately finite. For the moment, sustainment models such as that proposed by Jay Forrester and the Club of Rome's 1972 Limits to Growth (covered extensively in All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace) loomed in the near-distance.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

More Resources on Adam Curtis:

The Guardian: Adam Curtis argues TV needs 'new tools' to tell its stories

No comments:

Post a Comment